Wildfire & Mountain Sky

When the first European settlers came to America, they found

not the pristine forests so commonly depicted by Albert Bierstadt, Frederic

Church, and other Hudson River School painters, but rather they found a

landscape marked by fire.

As fire chronicler Stephen Pyne (1997) has observed,

human-set fires once cleansed the landscapes of North America, but today fires are

absent from regions like the Northeast that formerly relied on them for farming

and grazing; they have receded from the prairies, once near-annual seas of

flame; and they have faded from the mountains and mesas, valleys and basins of

the West.

Fire is a natural

component of the Gallatin-Madison range ecosystem. It is a driver of change

that influences the overall structure of the forest, its species composition

and its age class distribution. Fire helps drive the recycling of carbon and

other nutrients in the soil, and stimulates the regeneration of fire-dependent,

fire-adapted vegetation. For wildlife, fire removes the overstory of trees, causing

openings that release grasses and forbs as well as creating snags and tree

cavities for food, roosting, and nesting.

While wild fire is a natural process, it is commonly not

welcome in conflict with humans, and the values society places on private

lands, human-built structures, and desired natural resources (e.g., timber,

recreation, water supply). While prescribed fire is a useful tool, in

reality, its use is highly constrained due to risk of escaped fires threatening

private and state land, as well as federal lands.

Two influences on today’s forest, and our ability to

respond to wildfire, are noteworthy: 1) Smokey Bear and 2) the lure of building

next to wildlands.

The first influence is a decades-long policy of

attempting to prevent forest fire, as symbolized by Smokey Bear’s “Only You Can

Prevent Forest Fires.” Though well-intentioned at the time, it is now widely

acknowledged by researchers and managers that the policy of aggressive wildfire suppression has contributed to a decline in forest

health, an increase in fuel loads in many forests, and wildfires that are more

difficult and expensive to control (Donovan and Brown 2007). Fire suppression,

combined with other influences like climate change, insect pests, and diseases,

are contributing to vast changes in wildland vegetation with the result that

landscapes are drier, less resilient, and more likely to burn once ignited. The

number of large wildfires (>50,000 acres) has increased over the past 30

years, and wildfires are more intense than they were in the past.

The second influence is the lure of living next to

wildland. It sounds idyllic, and more and more people are choosing to live in

these natural areas -- referred to the wildland-urban interface (WUI).

Unfortunately, as more people dwell in the WUI, fire management becomes more

complex and the costs to fight wildfires and protect homes and human lives has

risen sharply as a result. Firefighters are forced to fight wildfires based on

private property and structures rather than the best way to contain fire or

guide the actual fire -- adding millions of dollars in cost and increased risk

to responding fire crews. Slowly efforts are building to incentivize private

landowners to become ‘fire-safe,’ to initiate hazardous fuels reduction

projects and increase landowner’s ability to defend structures and increase

firefighter safety.

But the question is not if a fire event will occur, but

rather a question of when, where, and to what extent. Forest and fuels

management cannot prevent fire, but it can greatly influence its behavior, intensity,

and extent.

The effects of two fires on Mountain Sky Guest Ranch are

plain to see.

Big Creek Wild Fire,

July-August 2006.

A lightning strike

on a power pole within State Section 16 started the fire. On July 29, 2006, it

was 97 degrees and 9 percent humidity. The fire was promptly reported and

managed by two U.S. Forest Service incident management teams and several local fire

teams. Full perimeter control was used on the north, south and east sides where

homes and private land are present. On

the west side, where there were safety concerns and no human values at risk,

very limited action was taken. The fire burned a total of 14,000 acres, 6,500

acres of national forest and 7,500 acres of private and state land. It was declared controlled on October 19,

2006 at a cost of approximately $3 million. On Mountain Sky Guest Ranch, the fire

burned some 1,720 acres in the north-central/Dry Creek area.

(photo taken from Leo Drive in South Glastonberry,

7-31-2006).

“I remember a

thunder storm on Wednesday, and high winds. Evidently a lightning strike smoldered

till the wind on Saturday ignited it. We sat down for dinner about the same

time that the wranglers turned out. Looking up from the picnic tables behind

the main lodge, we saw a huge plume of smoke northeast of the upper ranch. The

wranglers brought the herd back down and sent them to the lower ranch. The

decision was made to evacuate the ranch. And we did.” Randy Venteicher, MSGR

Head of Maintenance

Big Creek

Prescribed Burn (March 2004, September 2008)

The Big Creek prescribed burns were authorized by the

Gallatin National Forest, Paradise Valley Fuels Management and Prescribed

Burning Project Decision Memo, on April 7, 2003. The first prescribed burn, aimed at treating

a ≈430-acre area (map), was implemented during the last week of March

2004. Due to the fact that objectives

were not achieved with this burn, the area was burned again in September

2008. The 310-acre burn required about

130 acres of juniper slashing in 2007.

The burn was accomplished in a prescription burn window on September

14-15, 2008. In 2010, the riparian area between the upper bridge and the Big

Creek Ranger Cabin was burned to reduce conifer encroachment and stimulate

willow sprouting. Overall project goals were:

1.

Reduce conifer encroachment on grass and

sagebrush meadows and aspen stands

2.

Maintain area with their natural fire occurrence

and severity

3.

Public and firefighter safety during wildfire

events

4.

Allow fire to play its natural role in the HPBH

Wilderness Study Areas

5.

Provide and/or maintain existing defensible

spaces within the drainage to facilitate fire suppression tactics and staging

areas during wildfire events

Resources

Geoffrey Donovan and Thomas Brown. 2007. Be careful what

you wish you: the legacy of Smokey Bear. Front Ecol Environ 2007; 5(2): 73–79. www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs_other/rmrs_2007_donovan_j001.pdf

Susan Stein et al. 2013. Wildfire, wildlands, and people:

understanding and preparing for wildfire in the wildland-urban interface—a

Forests on the Edge report. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-299. Fort Collins, CO.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research

Station. 36 p. https://www.fs.fed.us/openspace/fote/reports/GTR-299.pdf

Ashley Sites, Zone Fire Management Officer, CGNF,

Livingston, MT. Source for information on 2006 and 2008 Big Creek fires.

Stephen Pyne. 1997. Fire in America: A Cultural History

of Wildland and Rural Fire. Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books. 680 pages. https://www.amazon.com/Fire-America-Cultural-Weyerhaeuser-Environmental/dp/029597592X

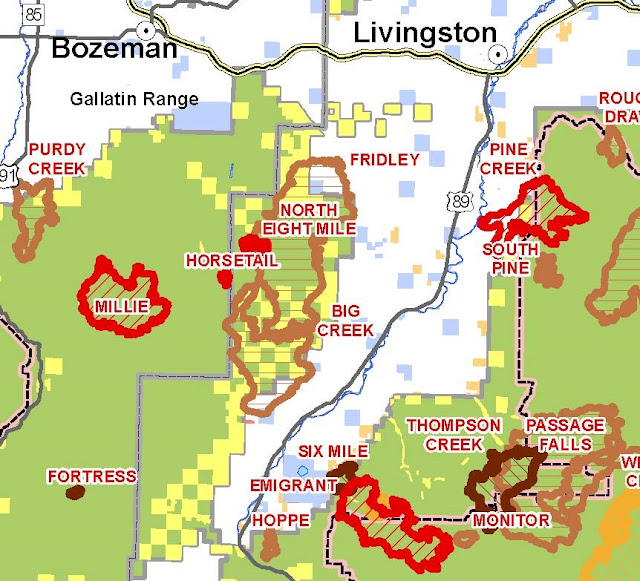

Custer Gallatin National Forest Fire History, 1980-2015

(>100 acres)

No comments:

Post a Comment